Greek Women’s History Lesson: Katerina Gogou

Don’t you stop me. I am dreaming.

We lived centuries of injustice bent over.

Centuries of loneliness.

Now don’t. Don’t you stop me.

Now and here, for ever and everywhere.

I am dreaming freedom.

These lines were uncovered from a lost poem of Katerina Gogou written after the Greek military junta (1967-1974). The verse, like much of Gogou’s poetry, reveals her commitment to free will and the imagining of a post-dictatorial Greece.

Gogou was born on June 1st 1940 in Athens, and from a very early age, she participated in children’s theatre. After graduating from high school, she enrolled in a series of drama and dance schools in Athens. However, given the strict censorship of the post-civil war monarchy, the only place she could make a living as an actress was in the Greek comedy industry, a major vehicle for the social reproduction of the statist, capitalist and patriarchal values of the time.

Most representations of Gogou therefore appear in film, where she starred as a proper 60s housewife in “Ο τρελός τα ‘χει 400” (“The Madman Knows”) (1968) and as a giddy romantic interest in “Δεσποινίς διευθυντής” (“Miss Director”) (1964).

However, Gogou’s film persona, while entertaining and laudable, had no relation to the teenage years she spent in downtown Athens during the post-civil war monarchy, an era characterized by strict censorship, police terror, and the island exile of political prisoners.

The smiley, benign characters Gogou played in her films would also not stand up to her more private life as a poet, for her writing displays her refusal to stand still long enough to be categorized. Indeed, Gogou’s anarchist spirit transcended into her poetry.

They shoot to kill.

They are shooting in the air, they cried

Then the small hole in front of the bus stop was filled with blood

They are only plastic bullets, they said

Then he fell

He has fainted, they cried.

Then he was motionless,

But they were already on their way. He was still,

But they had already taken the trolley-bus, and gone. Gone were they

Much of Gogou’s poetry comprised vitriolic depictions of Athens that were not in keeping with the leftist heroics and republican triumphs of the post-dictatorship years. Indeed, the gritty realities that Gogou laid bare were always expressed first and foremost in her poetry although you would never guess this from her work as an actress.

A still from Gogou’s role in “The Madman Knows”

It was to escape the pigeonholed roles she was so often cast in that Gogou cut herself off from cinema several years after making her last film, ‘Paragelia’ (1980). After several arrests and police interrogations, she honed in on her poetry; her disdain for the films she had starred in and the gender roles they perpetuated is clearly expressed in many of her poems. In fact, Gogou’s words convey the danger of being pinned down, dissected in terms other than your own and hence devalued.

What I have noticed is that Greek writing, especially poetry, can never be divorced from its historical, political, and cultural context. However, Gogou herself feared that in becoming a “poet,” her anarchist fight might be trapped within meter and rhythm, that poetry would make her “tired” and thus “an easy prey for priests and academics.”

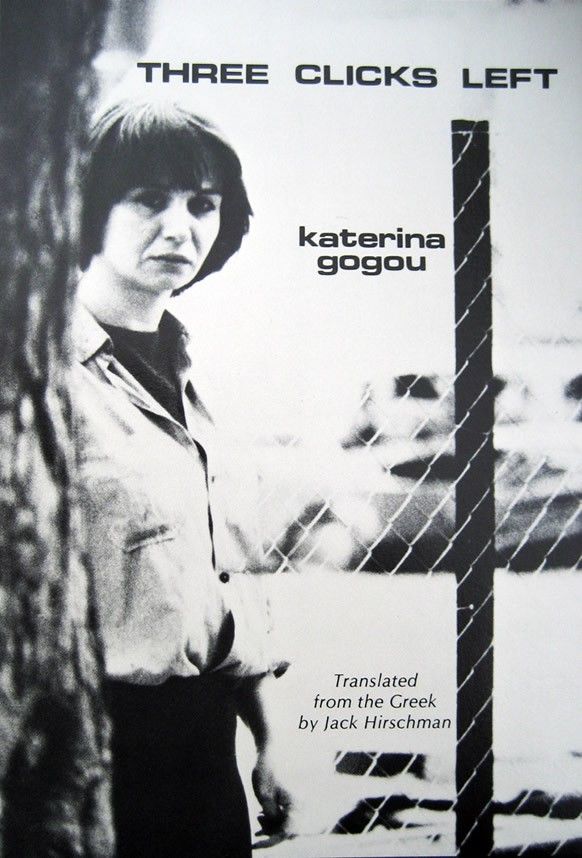

Instead, Gogou’s verses have become popular songs — anthems of a sort. Her first collection of poetry, “Τρία κλικ αριστερά” (Three Clicks Left, 1983) sold over 40,000 copies in Greece and has also been translated into English, quite a feat for a female poet who appears to fade into the background of Greece’s artistic scene.

Athens needs Gogou’s words more than ever now. They are testaments to freedom of expression beyond censorship, to the poetic expression of a female identity that goes beyond monolithic stereotypes, and to a country in (what seems like) a perpetual state of recovery. Gogou’s life ended far too early (she committed suicide at the age of 53), but I hope her words will endure and travel for many decades to come. They certainly traveled to me beyond all boundaries of time and geography.